The Art of Rubens and His Fascination With “Plump” WomenThe reasons behind his voluptuous nudes

- Ellen Michel

- Jul 4, 2022

- 5 min read

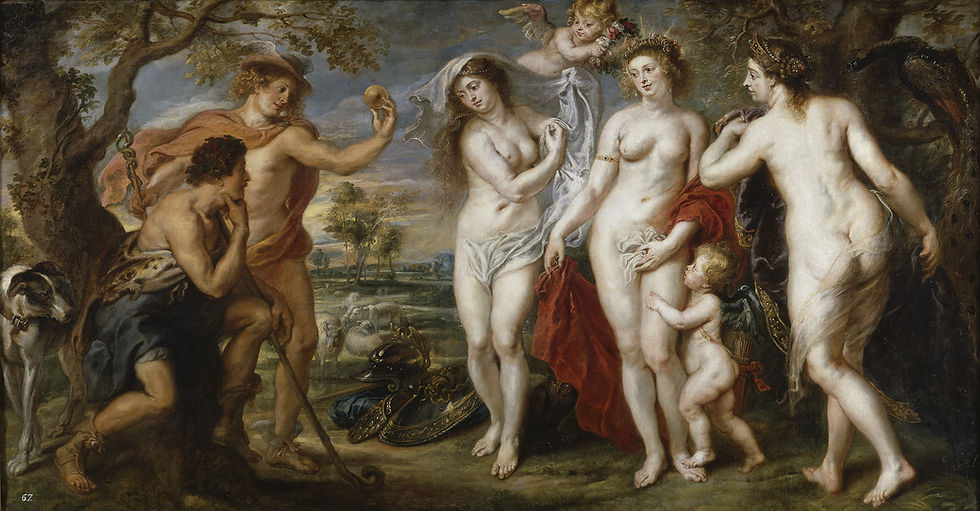

Judgement of Paris (between 1632 and 1635) By Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on oak wood. National Gallery, London. Image source Wikimedia Commons

The painting above shows three disrobed women posing in a beauty contest. The winner of the contest is being offered a golden apple as the prize.

Each of the women is arranged in a different way: notice how the artist has turned each figure in a different direction to show us the female nude from every angle: front, back and side.

Painted depictions of women from the brushes of Peter Paul Rubens, the Flemish artist who lived between 1577 and 1640, have become so recognisable for their full and shapely appearance that the term “Rubenesque” has been coined to describe the form.

Defined as “plump or rounded, usually in an attractive or pleasing way”, Rubenesque women populate his paintings in great numbers. Here’s another example, made a few years after the image above.

Judgement of Paris (between 1638 and 1639) By Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on panel. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image source Wikimedia Commons

This painting in fact shows the same scene, that of the mythological beauty contest known as the Judgement of Paris. Once again, the artist has portrayed three nude women in a variety of poses in order to explore (and perhaps expose) every aspect of their unclothed beauty.

But why was Rubens so fascinated with this particular type of female nude?

Well, it has something to do with circles, squares and horses, but we’ll get to that shortly…

A beauty contest

Let’s look at the subject first. The two paintings show the key moment in a mythological contest, where three goddesses are competing to be crowned “the fairest”.

The background to the story begins with an auspicious wedding. Everyone was included on the guestlist except for Eris, the goddess of Strife. Dismayed at being left out, Eris hurled a golden apple into the feast. The apple was inscribed with the words “To the Fairest” — and so began the contest to win the prized fruit.

The young prince Paris was chosen to be the judge. He was brought by Mercury the messenger god, who can be distinguished in the paintings by his winged hat and his caduceus or magic wand with two snakes entwined on it.

Judgement of Paris (between 1632 and 1635) By Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on oak wood. National Gallery, London. Image source Wikimedia Commons

Paris is shown as the seated male, depicted in rural clothing and holding a staff — since despite being a prince, he was raised as a shepherd. Before him, three goddesses present themselves: Juno, Minerva and Venus.

Juno, the right-most of the three women in both works, can be recognised by her peacock and her stately robes, since she was the chief goddess of Olympus.

Minerva, an ancient war goddess who fought for justice, can be seen on the far left with her shield and helmet.

And Venus, the goddess of Love, stands in the middle of the three with her attendant Cupid nearby.

Left: Judgement of Paris (between 1632 and 1635) by Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on oak wood. National Gallery, London. Image source Wikimedia Commons. Right: Judgement of Paris (between 1638 and 1639) By Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on panel. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image source Wikimedia Commons

Comparing the two paintings, it is interesting to note is how the later work — made in around 1639 — is an almost perfect mirror-image of the earlier, made some five years before.

So what was Rubens doing when he painted women with such idiosyncratic consistency?

The modest Venus pose

Looking at the two paintings, it becomes more obvious that the female nudes are all variations on the theme of the Venus Pudica. First of all, every figure is shown in a standing position. Each adopts a contrapposto pose, with the weight place on one leg and the pelvis is tilted.

An example of the “Venus Pudica” (modest Venus) type. The Capitoline Venus. Image source Wikimedia Commons

“Elegantia” was the ideal expression of female beauty, most readily portrayed through the traditional Venus Pudica (modest Venus) pose, where an unclothed female stands, usually with her left hand pulling a cloth over her genitalia whilst her right covers her breasts. Rubens made reference to this pose often in his paintings, drawing upon ancient models of female beauty. It was his belief that the bodies of ancient Greeks and Romans were closer to the perfection of creation, after which humankind had since declined. A theory of women as circles and horses Rubens was a widely read artist. Like many artists since the Renaissance, he was keen to seek underlying connections in the world of objects, humans and animals, and to express those connections in his paintings. Rubens found much inspiration in the writings of the Italian physiognomist Giovan Battista Della Porta (1535–1615) who theorised that the world of living things contained a fundamental coherence and pattern. Della Porta’s De Humana Physiognomia (1586) was of particular influence. Part of Della Porta’s project was to look for “syllogisms” in nature: for instance, in comparing a strong animal like a lion with other powerful animals like horses and bulls, he sought out common traits and essences. As a sign of strength, Della Porta recognised that each of these animals was broadly built. He therefore considered strong animals to correspond with the geometric figure of the square, the logic that provided an underlying principle behind all similar manifestations. Rubens used these ideas as the basis for one of his central tenets, that the dominant element of man was the square or cube, whilst the dominant element of woman was the circle or sphere.

Above Three Female nudes from Ruben’s Judgement of Paris

Rubens was also interested in the animal natures that he believed men and women carry within them. For women, the preordained animal was the horse — as expressed in his De Forma Foeminea (“On the female form”), a section in Rubens’ notebooks. He noted that the ideal woman, like the horse, had large black eyes and a long, broad neck. Rubens considered the horse to be similar to women because of its noble and elegant bearing. The horse is also “vain and proud, like a woman, fond of decoration and adornment, always absorbed by her own silhouette.” the circle and the horse as the essence of the female figure, Rubens was able to define his ideal woman as possessing “an abdomen which is slightly curved and decreasing down-wards, buttocks which are not stretched or hanging, but round, ample, firm and fleshy, a small womb, thighs that are plump.” As these mature paintings show, Ruben’s was clearly at a stage in his career where he felt at liberty to experiment with various arrangements of figures whilst also keeping to a “standard” way of capturing his subject matter. The plump bodies of the women in Ruben’s paintings were designed to highlight their goodness, desirability and desires, and fertility. For Rubens, female beauty was based on fleshy abundance, not on the lack of it, a trait that was not only desirable but noble too.

Left: Judgement of Paris (between 1632 and 1635) by Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on oak wood. National Gallery, London. Image source Wikimedia Commons. Right: Judgement of Paris (between 1638 and 1639) By Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on panel. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image source Wikimedia Commons

P Jones is the author of Great Paintings Explained, an examination of fifteen of art’s most enthralling images. Would you like to get… A free guide to the Essential Styles in Western Art History, plus updates and exclusive news about me and my writing? Download here for free.

Comments